Analysing business process pain points to get better requirements

Despite the ongoing process of business analysis maturing as a discipline, the question of getting requirements right is still debated on various business analysis related web sites. Poorly defined requirements are still quite common.

Enterprises have a lot of under-performing processes and legacy systems which require improvement or replacement to maintain competitive advantage, regulatory compliance or to keep technology up to date. These processes and systems exist in the business context which should be properly understood to ensure that the elicited requirements reflect the actual needs of the business, but this step is often missed or given only cursory inspection.

So, good requirements have to be defined in a clearly understood context, but how can this context be determined? Analysing pain points in the business processes can be helpful.

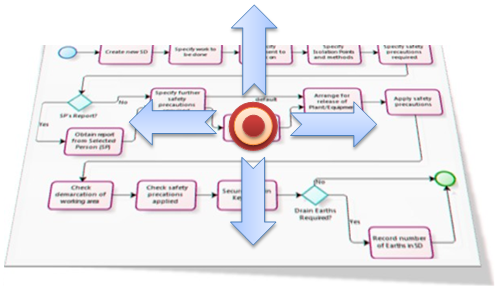

Have a look at the picture below showing a pain point somewhere in a business process. What can we learn from the pain point? Actually, quite a lot.

Center: the pain point

The pain point itself tells us about the problem that the business has to deal with. The scale of the problem shows how far the “wave of pain” travels within the enterprise.

Here is what we can learn:

- it explains the essence of the user’s activity,

- it helps us to refine the definition of the problem,

- write a proper problem statement,

- determine project and solution vision, and

- specify the requirements to the solution which would remove the pain.

Tip: Check out what business rules are valid for the pain point and write them down.

Up: business context

The move up from the particular business process through the layers of enterprise architecture lifts us to get a better view of the business context.

What we can find out:

- Impacted business users,

- Impacted business process,

- its dependencies and its boundaries,

- department,

- business function,

- line of business, and finally

- the enterprise.

Down: what supports the activity

The move down through the enterprise architecture layers tells us what supports the activity performed by the business user.

By doing this we can find out:

- what business service is provided to the user to fulfill his/her activity (software package, GUI),

- in which form the working data is available,

- what infrastructure supports the business service, etc.

Left: activity inputs

The move to the left allows us to understand what I call the “left-hand” causes because the inputs are typically shown on the left in diagrams.

Things to learn:

- inputs which are in place for the activity,

- sources of inputs (data, communication between people),

- what triggers the activity, and

- how often it happens.

Right: outputs and downstream activity

The move to the right lets us discover so called “right-hand” impacts on the next activity.

Things to learn:

- trigger for releasing the output,

- output data,

- necessity of communication,

- changes made to data (transformation during the activity).

Conclusion

The application of this approach has two main benefits. First, it helps maintain stakeholder engagement as you have answers to almost any questions. Second, you have a solid base to work on business analysis artifacts and cooperate with different specialists within a project team.

New! We have published a new book: A Navigator to Business Analysis.

Over 400 pages of practical, useful material will help you build your skills and advance your career! Find out more and get free excerpt.

Free course: BABOK 3 Navigation Maps

Subscribe and get an overview of the knowledge areas in BABOK 3. (Very occasionally, we may let you know about discounts and specials).